MY AMERICAN STORY

What’s your story?

My American Story: Jill Lafer

Women’s health activist Jill Lafer honors the strength and empathy of her Eastern European family.

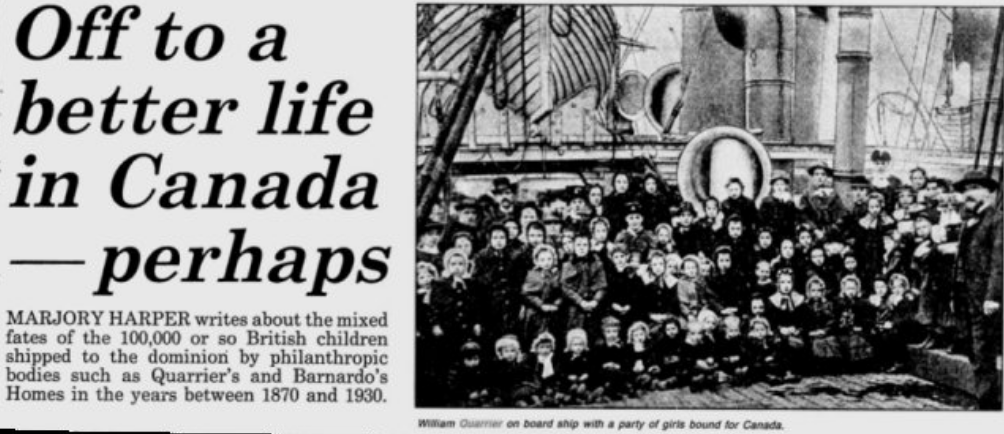

I can trace my ancestry to the mid-nineteenth century when my family emigrated from the Austro Hungarian Empire, Belarus, and Russia. Similar to other Ashkenazi Jews, they were fleeing repression and rampant anti-Semitism; they sought freedom and economic opportunity in America for their families. My great grandparents settled in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, and in Utica and Brooklyn, New York.

Town Hall of Glace Bay, Nova Scotia

Postcard of Utica, NY, 1934

Flatbush Avenue, Brooklyn, 1918

A sign from my great grandparents’ store: Rosenblums

Around the turn of the twentieth century, my great grandfather Simon Rosenblum opened a dress shop in Glace Bay, Max Benjamin toiled as a peddler in Utica, Joseph Weinstein opened a tailoring shop in Brooklyn, and Jacob Stober, the last to arrive in about 1910, was a peddler who eventually owned several fine dress shops in Montreal. These peddlers and shopkeepers watched their families flourish; their children and grandchildren became doctors, lawyers, engineers, judges, hoteliers, songwriters, and entrepreneurs. They became part of the fabric of the United States and Canada like so many other immigrant families from all over the world.

The stories of the women in my family have strongly influenced my life and my values.

My maternal Grandmother, Miriam Weinstein Benjamin

My maternal grandmother, Miriam Weinstein Benjamin, born in 1908 in Makow Poland, sailed on the SS Rotterdam in 1918 to New York. She lived with her father, ailing mother and five siblings in a small apartment behind her father’s tailoring shop in Brooklyn. She studied accounting while employed by an Investment Advisor for the Brenner Brothers, who were fur traders. Years later, when her mentor retired she became the Brenners’ sole financial advisor and one of the first women on Wall Street. The Brenners sold fur skins, and my grandmother issued credit and was integral to the founding of Alixandre and other prominent furriers. As the first woman President of an American Technion University chapter, she also raised my mother and aunt. According to my mother, she never spoke of her childhood in Poland-- she only wanted to be American. However, she once told me that she had borrowed a dress for her passport photo from her cousin, who subsequently perished during the Holocaust.

My Canadian great grandmother, Ethel Rosenblum, operated the store in Glace Bay. The eldest of her eight children, my grandmother Sarah was born in 1900, raised four sons, and also worked with her husband, Jacob, in Montreal. They instilled a deep love of learning, family, and hard work to their children and grandchildren. Until my grandmother passed away in 1990, we spoke regularly, visited each other in New York and Montreal, went to theater and museums together and discussed life, family and values.

Jacob & Sarah Stober and their four sons, approx. 1940

My great grandmother, Esther Rosenblum with her children and some sons and daughters in law, 1938. My grandmother, Sarah, is top row far left.

Lou and Miriam Benjamin, My mother, Ruth, far left and her sister.

I was fortunate to have two loving grandmothers who had a tremendous impact on me as a young woman, but my father had the greatest impact of all. He was my life champion.

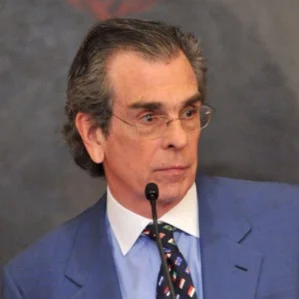

My father, Dr. Gerald S. Stober

My father, Gerald Stober, was the only one of Sarah’s four sons to leave Montreal. In spite of the Jewish quota he graduated McGill Medical School and selected New York City for his residency. He met and married my mother Ruth; they moved to back Montreal where I was born. In 1958, they returned to New York for better economic opportunity. My father was an OB/GYN, a founder of New York-Presbyterian Queens Hospital and was the first to permit fathers to be present during Caesarean sections, a right for which he vigorously fought. My mother managed his practice for 30 years and, like generations before them, they worked together to create a good life for their three children.

Ruth and Gerry Stober dancing, circa 1975

He was always a champion of women. Prior to Roe v. Wade my father witnessed women dying and irreparably damaged from botched illegal abortions. He understood the difficult choices women made between their families and careers. His patients included women of color and immigrants who were primary breadwinners—similar to so many women I have spent decades advocating for at NARAL and Planned Parenthood. He often spoke to me about the difficult daily lives of his patients as compared to my life of privilege, and he opened my eyes to the lives of others less fortunate. Although I didn’t know it at the time, this message was the beginning of my political awareness.

The aspirations and dreams of my relatives who arrived here 150 years ago have been fulfilled. Like so many immigrants to this country, they were industrious women and men. They were fortunate to be accepted at our borders. America gave them the freedoms and opportunities to flourish and in turn, they became proud, engaged, and productive Americans.

About the Author:

Jill Lafer has been a leader in the women’s reproductive rights and health movement for over 35 years. Jill is the former board chair of Planned Parenthood (“PP”) Federation of America and currently serves on the PP Action Fund Board, the PP PAC and the Tri State Women’s Maxed Out PAC. Previously, Jill served as board chair of NARAL Pro-Choice New York, was a board member of the National Institute for Reproductive Health and was treasurer of The No Bad Apples PAC founded by New York State Senator Liz Krueger.

Since 2009 she has served as a mayoral appointee (Bloomberg, DeBlasio) to the Central Park Conservancy Board. She has also served on the boards of The Children’s Museum of Manhattan, New York City Opera and Guild Hall in East Hampton.

She is a fellow at Stanford University’s Distinguished Careers Institute. Jill has been a guest speaker at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, Harvard Business School, Columbia business School and UCLA’s Anderson School of Management.

Jill’s background is in the business sector. She was an auditor for Arthur Young and Company, worked in strategic planning for Citibank and co-founded a consumer licensing business, Hoffman/Lafer Assoc. L.L.C. In June 2020 she founded Bandon Partners LLC, a consulting firm for not for profit organizations. She is currently consulting to rePRObymama.film, a Midwest based film festival dedicated to women’s health, rights and justice. She is married to Barry Lafer and has three children and two granddaughters.

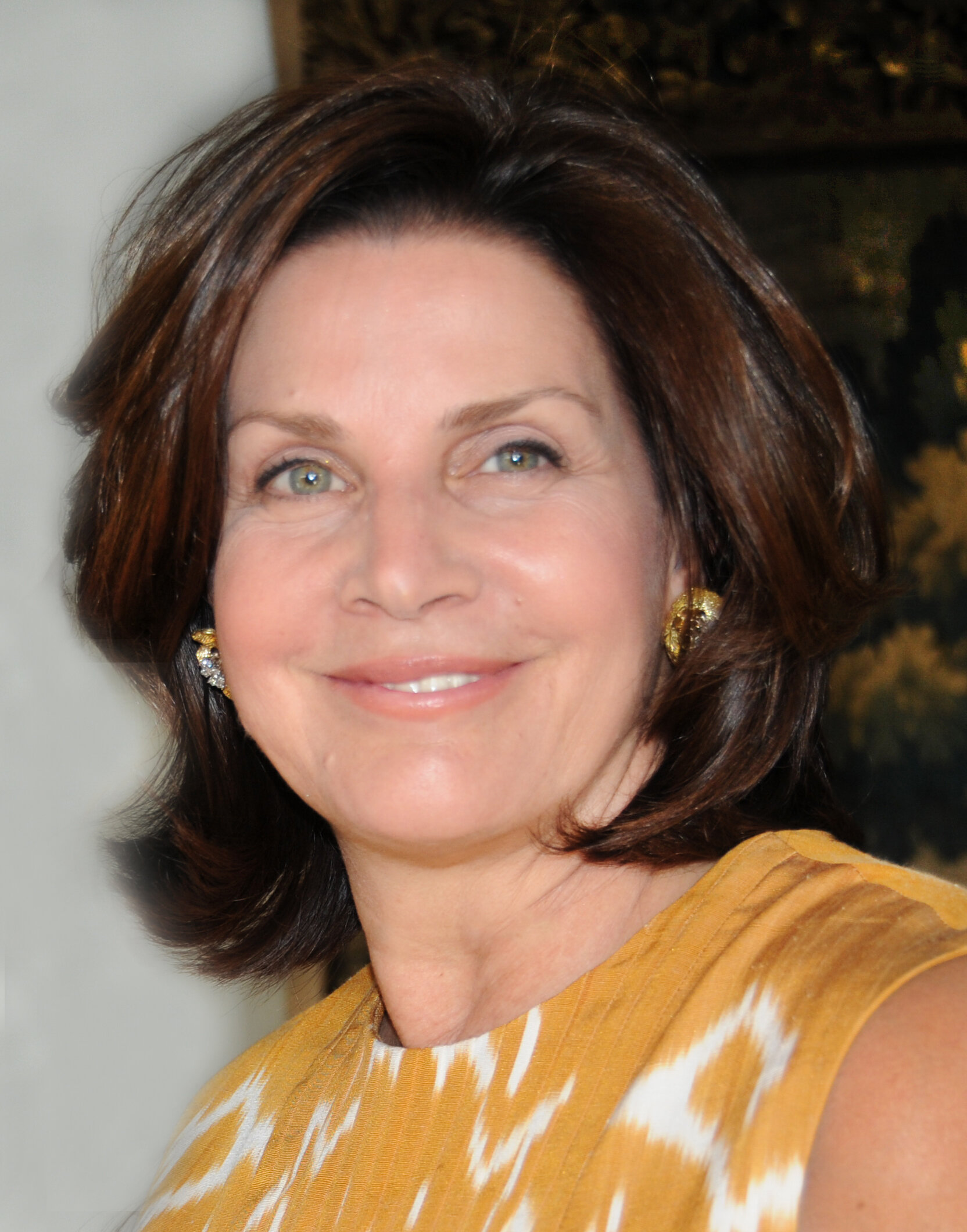

My American Story: Pat Schoenfeld

Pat Schoenfeld up as a true New Yorker, spending time with her Irish and Russian grandparents, before she entered the world of Broadway alongside her husband, theater legend Jerry Schoenfeld.

The future “Mrs. Broadway” with Irish and Russian heritage grew up as a true New Yorker.

What is my American Story? How can I answer that question? One must understand: in my story, people weren’t told their family history.

Much of what I know now is what I have figured out from family stories, without much detail. When I grew up, being an American meant you were special. Being an American wasn’t what you were, it was a fact in addition to who you were. If I was ever asked what I was, my answer would be, “I am a New Yorker.” At that time, we would not have even thought to say, “We are American.”

The years of my childhood were the Depression years and the World War II years. Not only did we not travel outside of our area, we only met people who were refugees from WW2-ravaged Europe and no one talked about where they came from. My mother would say, “It is impolite to ask those questions.”

The New York City Victory Parade, celebrating the victorious end of WWII on Fifth Avenue, Jan. 12, 1946

Broadway, 1950

I knew my mother’s grandfather, my great grandfather, came to America from Russia in the 1870’s. He went back there to get his wife, but she was pregnant at the time, so he returned, now with his wife and newborn son, my grandfather Charles Rosenberg, around 1885.

Shops on Amsterdam Avenue, Upper West Side of New York, 1949

Both my parents were born in New York. My mother, Mabel Rosenberg, grew up on the Lower East Side. The family lived there because her father Charles, born in Russia and raised in New York, grew up to become a lawyer and wanted to be able to come home for lunch with my grandmother Fanny. Though, when I knew both my grandparents they lived in gorgeous old apartments on the Upper West Side.

My father, S. Peter Miller, grew up in a mansion in Brooklyn. His father, my grandfather Harry, was in the real estate business and owned major properties in Manhattan: all of this was lost in the Depression.

New York schoolgirls relax, 1953

Though I knew my grandfather very well, I know almost nothing of his personal history, except that my family said he came over from Ireland, and was a very non-practicing Jew. All I knew of my father’s family background, and what was important to me, was that my father’s mother, my grandmother Sara, made wonderful French Toast. You could smell it when you got off the elevator in their apartment. She was the story book grandma: baking cookies and sending them to me in college, buying me the hair ribbons my mother didn’t love in my hair, and being there to give me lunch when, in Jr. High, I fell in love with a boy that lived in their building.

I was born in 1929 on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, New York. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in the White House for almost all of my young memory. He was our father; our king; our leader. And, like Trump supporters believe in my world today, back then if you didn’t support FDR, you were un-American and not part of my young world.

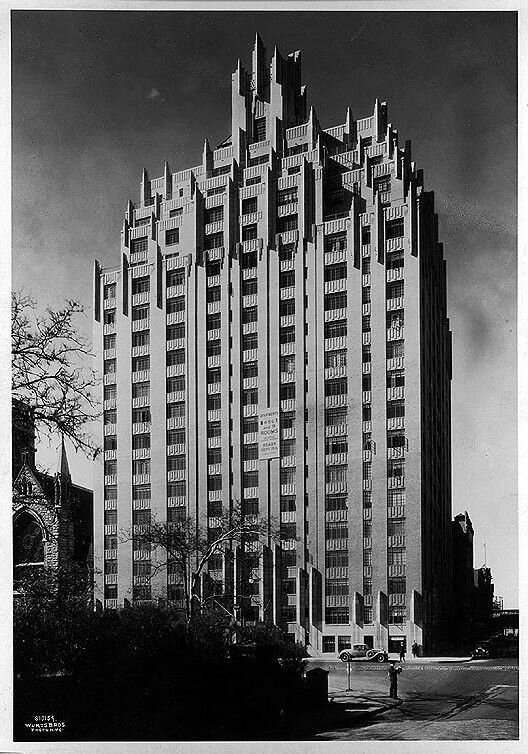

A new apartment building on Central Park West, built 1930

What was important to me growing up at this time was that my family was different, because I was second generation: my family were all Americans. My friends’ families all came over later than mine, and my friends were all first generation immigrants. They and their families had come to America to seek their fortunes in the mid 1920’s and 1930’s. They were all in the garment trades or real estate. They all lived in big apartments on West End Avenue or Central Park West. They were richer than we were. We lived in a small building in a 2 bedroom apartment on West 78th Street off Riverside Drive.

Horseback riding in Central Park, 1940’s

My friends and I all went to private schools. We were the first generation to go to private schools not because we were rich, but because our parents were concerned about our education. The public schools were changing. Class sizes were getting bigger and our parents didn’t think we were getting the attention we needed in the public schools.

This was the beginning of my understanding that, as established New Yorkers, my family was different. My parents had an American attitude, they were open and welcoming to all my friends. My friends’ parents had a European point of view, they brought up their children in a much more reserved and regulated way, and they were much less open to me and our other friends.

And my parents’ attitude was different because they both were born and brought up in New York; they worked hard and gave my sister Cynthia and me a knowledge that we could do or be anything we wanted. How rare it was that my father took a major interest in our development! He took us out every Sunday to tour Manhattan, go horseback riding in Central park and play tennis.

I graduated from high school in 1946. I told my parents I had to get away from the homogeneous world I grew up in. I didn’t want to go to Vassar, Wellesley, or Smith, places where all the girls I knew were going. Somehow my school advisor suggested that I go to Ohio Wesleyan University.

I was 17 years old, and had never even left the East Coast, and my father put me in an airplane, alone, to Cleveland. From there I took a bus to Delaware, Ohio. I can’t believe that this teenager had the guts to enjoy and embrace that experience. I lasted for 2 years, years that taught me so much. I was not pledged to a sorority because I was a Jew. I recall visiting my best friend, who lived an hour away from school, and her family had no indoor plumbing.

Two students on the NYU campus, 1940

Years later, when my daughter wanted to go off somewhere with her boyfriend, and I did not let her go, I told my mother that I had no idea how she managed to let me go so far from home at such a young age. She told me,“Patsy darling, I taught you everything I knew until you were 12, and then I trusted you.”

Eventually, I met and married the man whom I spent the rest of my life with -- Jerry Schoenfeld, who was first a lawyer and then became one of the most influential figures in American theatre, renowned for his contributions to Broadway through his leadership at the Shubert Organization.

Jerry lived just one block away from me! I knew him from the neighborhood. He had just returned from the University of Illinois after having served in World War II. Jerry was five years older than me, so I had none of the experiences that he had at that time. He was at NYU Law School and I, having returned from Ohio, was then an undergraduate at NYU School of Education.

I would see Jerry in the subway and would join him in our journey to school. We became ‘friends’, but not ‘sweethearts’. It was so rare to have a real ‘boyfriend’. We didn’t even date - until I invited him for dinner. It was during an intersession (now called a January-term) and his parents were in Florida. When I invited him, he told me, “I don’t go to girls’ houses for dinner.”

“I always have friends for dinner,” I said.

That started a long and wonderful romance. We were finally able to marry after Jerry finished Law School - he graduated 2nd in his class, Cum Laude. At the time, none of the big Law Firms would be open to him. They didn’t take Jews. He got a job in a very small firm: they were only 3 old men, one law clerk, a senior partner, a young law clerk, and Jerry. This firm represented the Shuberts. And the rest is history.

Jerry, right, with Bernard Jacobs of the Shubert Organization, left, and Jerome Robbins, director and choreographer

Jerry, left, with Bernard Jacobs, center, and Philip Smith, then CEO of The Shubert Organization, 1970

Jerry’s father Sam came from Vienna, although I think it was by way of Poland. I’m sure that’s where they picked up the name of “Schoenfeld”. His mother was born in New York and her family were not so pleased when she wanted to marry Sam: he was not born in New York so he was not “worthy”.

How sad it is that we were not told the stories of how our relatives came to America and their quest for freedom!

No one would talk about this. I remember I had a wonderful French friend whose family was pursued by the Nazis. She and her sister had an amazing story to tell about their rescue and how they came to America, but she would never fill in details or ever talk about her history. It was only very late in her life that she felt able to tell the story to her children.

Now there are many TV programs and websites that are encouraging people to investigate their family histories, but I have never done that. My daughter Carrie; her husband and children and grandson, my nieces and nephews are my very small but very close family.

My history is a one of a Native New Yorker, and therefore a very proud AMERICAN.

About the author:

Patricia Schoenfeld was born and raised in New York City and has had a long and varied career in the visual and performing arts. After earning her degrees in Child Development, she began teaching at schools on the Lower East Side, before becoming one of the first Guidance Counselors in New York Elementary Schools. She later taught at Hunter College, and worked on an early educational TV program in the late 1950’s.

As an accomplished ceramic artist, her work has been included in many private collections and exhibited in galleries throughout Connecticut and New York. In 1974, she began working with Cornell Capa to establish the International Center of Photography. As a founding staff member of ICP, she launched the book store and the publications department, began the membership and intern programs, and assisted with public relations and corporate memberships. Upon her retirement in 1987 she joined the ICP Board of Trustees where she and other Board members helped cultivate ICP into the organization it is today.

My American Story: Kati Marton

After witnessing the arrest of her journalist parents in Soviet controlled Hungary, and tanks driving through the streets of her hometown, Kati Marton arrived in the USA on her 8th birthday.

[Kati, center,with mother Ilona and sister]

I’m a refugee. I came to America with my parents as a little kid, and had no connection or roots or history in America. No one in my family did, we were complete strangers to this land. I did not speak any English. My parents considered America to be our last, best hope. They had survived the Nazi Occupation of Hungary, which my grandparents did not survive. My grandparents perished in Auschwitz, so I have never even seen photographs of them.

[Newspaper clipping announcing the arrest of Kati’s parents in 1955]

[Leaflets like these were distributed in support of Radio Free Europe’s program to transmit news programs past the strict censors of Soviet governments]

[Soviet tanks in Budapest, 1956]

[Revolutionaries capture a Russian tank, Budapest, 1956]

When I was six years old, I was a witness to my parents’ arrest. They were imprisoned under false charges of being CIA agents, but their real crime was that they were good reporters covering a lot of bad news as the Soviets occupied and slowly took control of Hungary.

[One of Kati’s first English lessons was memorizing the commercial for Ipana toothpaste]

This was in the aftermath of the second World War, the 1950’s and the coldest days of the Cold War. My father was [working for the Associated Press], and my mother with [United Press International] in Budapest, which was why they had to be jailed: they were the last independent press behind the Iron Curtain. I did not see my father for two years, and my mother for a year. The worst thing was that no one talked about what happened to them, because it was a rather common occurrence for people who the government deemed to be “Enemies of the People” to disappear.

My parents were sentenced to very long prison terms. Then came the Hungarian Revolution and they were free - they went right back to work as reporters. So again they disappeared, covering the biggest story of their lives, which was the freedom fight that got rid of the Russian occupation. But that freedom lasted ten days and then the Soviet troops came back. As young a kid, I saw tanks in my hometown and strange soldiers patrolling my neighborhood.

[Kati, 10, left, with her family in Vienna, 1957]

Still, my parents did not want to leave our country until they were tipped off that they were going to be arrested again, and my mother simultaneously discovered that she was pregnant with my younger brother. They finally started making plans to escape - we had several misadventures. Over the years, my parents had spent a small fortune on guys who were going to smuggle us out of Hungary through Yugoslavia into Austria and something always happened. Finally, though, we did succeed and it was a year of such turbulence that I didn’t go to school for a whole year.

[Endre and Ilana Marton, right and center, receive the George Polk Journalism award for their work covering the Hungarian revolt shortly after arriving in the U.S. in 1957]

[After we arrived,] everybody was extraordinarily busy with acclimating ourselves. But we had nothing, I mean nothing. We came with four suitcases. My parents let my sister and I pack our own suitcase, and of course I filled mine with toys and a couple of choice and entirely impractical items of clothing. But I thought that was very sweet of my parents to let us bring something of our life and of our former homeland with us. All of which to say, we were bringing nothing to this country. We were not nuclear physicists, we were not Norweigan, we didn’t speak English, and yet we have collectively managed to live very productive lives.

My father and mother both got a bunch of journalism prizes for their work, subsequently. America really took a chance with us because we did not bring wealth, we did not bring any type of technical background. We were just very eager to Americanize. And to finally breathe easy.

[Kati, center, with her parents and sister in Hungary]

We were the modern refugee family, with the two little girls, and the pregnant mom, and the very handsome reporter dad - who soon became the Associated Press’ Senior Diplomatic Correspondent.

And my mother decided she was going to start a new career in her mid forties. She had been a reporter too, for a rival news agency, but she decided that with a little baby due and two little kids who were traumatized, which was myself and my sister, she would start a more, shall we say, conventional life as a high school French teacher.

I think [the transition] was tough for my parents, they were in their forties, middle-aged. And the toughest thing for them was the culture and the music. And we, the kids, tried to get them to listen to our music and explain why The Beatles were better than Beethoven, but they weren’t buying it. They were willing to put up with a lot, in terms of having noisey American kids, because they had a tremendous sense of gratitude about the second chance they were getting here.

[Ilana and Endre Marton in Washington D.C., 1970’s]

And these days I have to admit that as much as I miss my parents, I am kind of relived that they’re not here because this is a passage in our country that would shock them. And I can’t even imagine what they would think of the way the press is treated now and being called ‘Enemies of the People’. It’s sad to say that is a phrase that has reentered our language these days, as the press is deemed to be the enemy of the people. Only the people now are Americans. That would come as a total shock to my parents. So would the nastiness of the conversation between and among Americans, because we lived in a fairly ordinary Washington suburb where I am sure that it was roughly 50/50 Republicans and Democrats. Nobody either cared or knew who voted for Kennedy or who voted for Nixon. It was just a part of the American deal that you have your party and we were welcomed into this neighborhood.

About the author:

Kati Marton is an acclaimed journalist and author, as well as an activist advocate for human rights and the freedom of the press. She is an award winning former NPR and ABC News Correspondent, the former chairwoman of the International Women’s Health Commission, a director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, and a member of the Council on Forign Relations. Marton has published eight books, which have been translated into five languages. Her Cold War Memoir Enemies of the People: My Family’s Journey to America was a National Book Critics Circle finalist in 2009.

My American Story: Kati Marton

In September, 2019, Kati Marton sat down with The Common Good to tell us her American Story, and give us some of her insights into the lives of immigrants, journalists, and activists behind the Iron Curtain and today.

In September, 2019, Kati Marton sat down with The Common Good to tell us her American Story, and give us some of her insights into the lives of immigrants, journalists, and activists behind the Iron Curtain and today.

[Kati, center,with mother Ilona and sister]

TCG: This is Zeena recording for The Common Good podcast, My American Story. Today we have Kati Marton, and she’s going to be telling us about her American story. As you know the project and the aim of the story is to celebrate our diversity as a nation of immigrants and the great American melting pot. And to collect stories from individuals, and recognize where we all came from; all of the journeys, the good, the bad, the beautiful, the sad, all of it. So I’ll just start off with a very, you know, looming question which is, where are your ancestors originally from? And what do you know about their roots?

[Newspaper clipping announcing the arrest of Kati’s parents in 1955]

Kati: Well, I’m a refugee. I came here with my parents as a little kid, and had no connection or roots or history in America. No one in my family did, so we were complete strangers to this land. I did not speak any English. I was 8 years old, and in fact, it was 8th birthday when we landed in a special refugee camp set up on the New Jersey Turnpike. An army base called Camp Kilmer, that was set up as an emergency measure because there were so many of us fleeing the Soviet occupation of my homeland of Hungary. We were given refugee status, because my mother and father had both just been freed from jail. They were in prison on fake charges of being CIA agents. Their crime was that they were good reporters covering a lot of bad news as the Soviets occupied and then slowly took complete control of my homeland of Hungary. This was in the aftermath of the second World War. We’re in the fifties now and the coldest days of the Cold War. And I was a witness to my parents’ arrest, which was a fairly traumatic event.

TCG: How old were you?

[Nazi troops occupying Budapest, 1944]

Kati: Six years old. I did not see my father for two years, and my mother for a year. The worst thing was that no one talked about what happened to them, because it was a rather common occurrence for people to disappear who the government deemed to be enemies of the people which is the title of my book. It’s sad to say that is a phrase that has reentered our language these days, as the press, which my parents were a part of, is deemed to be the enemy of the people. Only the people now are Amricans, so that would come as a total shock to my parents who considered America to be our last best hope. They had survived the Nazi Occupation of Hungary, which my grandparents did not survive. My grandparents perished in Auschwitz, so I have never even seen photographs of them.

But they considered America to be our sanctuary and our last stop, so that’s why we made that long journey which ended on the New Jersey Turnpike on my birthday! It was a wonderful day, and I’ll just tell you because I can’t resist. That day when the first Marine saw that it was indeed my birthday, he from somewhere produced a silver dollar. By the time I was a fully processed little refugee kid, I had collected 6 silver dollars, which my mother kept for me for years. And I wish I knew what happened to them. But it was just such an amazing welcome to this country. And I thought, ‘hm I’m going to like it here.’

TCG: Would you say that from arriving, kind of, how long did it take you to feel like that you were a part of this country? Did you automatically embrace the American spirit?

[Hungarian refugees arrive at Camp Kilmer]

Kati: I wouldn’t, you know, I was in a complete daze. I would say shock, because so many things happened that year. My parents were restored to me, they were free. They had been sentenced to very long prison terms. Then came the Hungarian Revolution and they were free. And they went right back to work as reporters. So again they disappeared, covering the biggest story of their lives, which was the freedom fight that got rid of the Russian occupation. But that freedom lasted ten days and then the Soviet troops came back. And so, I was a kid who saw tanks in my hometown which was a pretty traumatic thing to see. And strange soldiers patrolling my neighborhood. my parents did not want to leave our country until they were tipped off that they were going to be arrested again. And my mother simultaneously discovered that she was pregnant with my younger brother.

So, they started finally making plans to escape. And we had several misadventures. My parents over the years, in fact, I didn’t know this until I was older, had spent a small fortune on guys who were going to smuggle us out of Hungary through Yugoslavia into Austria and something always happened. So finally, we did succeed and it was a year of such turbulence I didn’t go to school for a whole year. And I didn’t speak any English, so I proceeded to start watching American TV. My first English lesson was memorizing all of the commercials.

TCG: Do any commercials stick out in particular?

[Hungarians fleeing the country in 1956]

Kati: Oh Gosh, don’t get me going! Yes! Brusha brusha brusha use the new Ipana! It’s dandy for your teeth. So, that was Kati, the refugee. And, by the way, I didn’t want to be called Kati. I wanted to be called Katie. So that lasted for about a year. I was Katie Marton.

TCG: Very American.

[One of Kati’s first English lessons was memorizing the commercial for Ipana toothpaste]

Kati: Nevertheless, every September in my elementary school the teacher would ask me to stand up and say ‘Class, this is Kati our Hungarian refugee.’ And I would immediately be beet red, I was so embarrassed. Then I would stand up and take a bow. It was meant lovingly and people were just so kind to us! We were kind of the modern refugee family, with the two little girls as pictured on the cover of that book. And the pregnant mom and the very handsome reporter dad who soon became the Associated Press’ Senior Diplomatic Correspondent.

And my mother who decided she was going to start a new career in her mid forties. She had been a reporter too, for a rival news agency. My father was [Associated Press] and my mother was [United Press International] in Budapest which was why they had to be jailed because they were the last independent press behind the Iron Curtain. She decided that with a little baby due and two little kids who were traumatized, which was myself and my sister. She would start a more, shall we say conventional, life as a teacher of French in high school. A high school French teacher. So everybody was extraordinarily busy with acclimating ourselves. But we had nothing, I mean nothing. We came with four suitcases. My parents let my sister and I pack our own suitcase, and of course I filled mine with toys and a couple of choice and entirely impractical items of clothing. But I thought that was very sweet of my parents to let us bring something of our life and of our former homeland with us. But all of which to say, we were bringing nothing to this country. We were not nuclear physicists, we were not Norweigan, we didn’t speak English, and yet we have collectively managed to live very, without beating my own drum, very productive lives. My father and mother both got a bunch of journalism prizes for their work, subsequently. And you know, America really took a chance with us because we did not bring wealth, we did not bring any type of technical background. We were just very eager to Americanize. And to, you know, finally breathe easy.

TCG: And did you find, I know you mentioned everyone was very kind to you and your family, growing up here as a refugee, what kind of challenges did you personally face and did you ever encounter anyone who was not so kind to you? And what was that like?

[Kati, 10, left, with her family in Vienna, 1957]

Kati: You know kids can be nasty. And I spoke with an accent and I particularly didn’t want to bring kids home, because my parents were so European. They were very old world and rather formal. My father, when I was a teenager and first started getting interested in guys, you know none of them looked right for my father. They all wore jeans that looked like they had fresh paint on them and shoes without socks. He would give them the once over and they would wither in terror and never come back. So, I started meeting people elsewhere. But, in fact, it turned out that my friends, because they now tell me that so many years later, loved coming to my home and loved hearing my parents’ stories. And history, because my parents had lived such full lives. And had so many interesting tales to tell and [my friends] loved the exotic atmosphere in this Hungarian home. I [had] lived most of my life in America by now but I was raised in a little separate world, a little Hungarian world and it didn’t seem to in any way disturb my Americanization. I had this other part of me that became over the years even more important as I grew to be a more confident American woman. I really began to draw, strangely enough, closer to my origins. And once I became a reporter for NPR and then with ABC News, I started weaving my own story into my reporting. And I remember when I became a foreign correspondent for ABC News, I was Bureau Chief in Germany. I did a five part series from Hungary. It was the first time they sent a reporter, it was still the Cold War, it was in the late eighties right before the wall fell. And ABC News sent me to Budapest to do my own story. And every night on World News Tonight, there I’d be standing in front of my old house, my school, like that. And so, it became very much apart of who I am. And I think that as a result, it feels strange to say, I feel more grateful to this country. [Then I would] if I would have to just slam the door on my own personal history and on my parents’ history. I wove it into the fabric of my new identity and I think that’s what America is really about. You get permission to do that, to be proud of what you bring here. And in fact, I think that it made me who I am.

[Endre and Ilana Marton, right and center, receive the George Polk Journalism award for their work covering the Hungarian revolt shortly after arriving in the U.S. in 1957]

TCG: So, let’s transfer over a bit to Kati the adult. So, you moved here as a young child, you Americanized with your own identity intertwined with it. How did that intertwined identity affect you going forward with your jobs, with your various paths in life? What was that like?

Kati: My refugee history was always a big piece of my identity. And my dream as early as my teens was to become a journalist, because that’s what my parents did and I so admired their lives and their courage in reporting under pretty dangerous circumstances. I mean, they paid a huge price. They went to jail for reporting the news. That was not a part of my ambition, to go to jail covering the news. But I did want that life of constant changing of environments and adventuresome life. I couldn’t imagine a different life. I kind of toyed with the idea of becoming a diplomat, because that too would have taken me out into the world. But the news business was the most tempting thing. So even while I was in George Washington University getting my Master’s, I heard about this new network that was coming into being: National Public Radio. And so, I applied and I was one of six people that put All Things Considered on the air, while I was still a grad student - so that would have been 1973. And so that was my launching pad, and it was kind of wonderful because it was just a small group of us and everybody did everything.

[Kati, center, with her parents and sister in Hungary]

I learned to cut tape, edit film- I was NPR’s first diplomatic correspondent as well which meant I had zero experience. Somebody one day handed me a giant tape recorder and said “Cover the briefing at State, the noon briefing.” And, to my enormous embarrassment, my father (who’s beat this was), as the senior guide in the diplomatic press core, was so excited that his little girl was going to be part of the team. He would always sit in the front row and save me a seat and it was the last place I wanted to be. I wanted to prove that I was doing this on my own, which I was, but everybody assumed [it was] “oh daddy’s girl getting her way.” So I would always wait until the briefing started and creep in and sit in the back and not sit next to my father. But, yes definitely, my personal history shaped my identity. I was not held back, we’re now in the late seventies, and girls were still meant to get married and I mean, young women were supposed to get married and become mothers and homemakers. I wanted that, but it was never going to be the main event. The main event was going to be self-fulfillment and a family too. I didn’t see why those two were in conflict, because my mother, who had been a reporter and been a jailed reporter, had been a very good role model.

TCG: Did your parents, in their time coming to the states, do you think they identified with the American identity as much as you did? Could you expand a bit upon their experience?

Kati: I think it was tough for them. They were in their forties, so middle-aged. And the toughest thing for them was the culture and the music. And we, the kids, as soon as there was a brother too, tried to get them to listen to our music and explain why The Beatles were better than Beethoven. They weren’t buying. They were willing to put up with a lot, in terms of having noisey American kids. Because they had a tremendous sense of gratitude about the second chance they were getting here. And these days I have to admit that as much as I miss my parents, who passed away a decade ago, I am kind of relived that they’re not here because this is a passage in our country that would shock them. And I can’t even imagine what they would think of the way the press is treated now - [the] “enemies of the people” thing. And about the nastiness of the conversation between and among Americans, because we lived in a fairly ordinary Washington suburb where I am sure that it was roughly 50/50 Republicans and Democrats. Nobody either cared or knew who voted for Kennedy or who voted for Nixon. It was just a part of the American deal that you have your party, and we were welcomed into this neighborhood.

[Ilana and Endre Marton in Washington D.C., 1970’s]

I remember my sister and I used to put on plays for all of the neighbors because we had frankly come from a family where culture was hugely important. My uncle was the conductor of the Hungarian Opera, for an example. We were a little bit ahead of our peers in terms of, you know, literature and art and so on. We would put all the neighborhood kids in lesser roles. We would save the bigger roles for ourselves. But everybody in the neighborhood would come and bring their chairs to our backyard and we would put on Shakespeare. We would put on operas and[things] like that. And there was no sense of this great divide that’s opened up. I never felt that we were either better or worse than anybody else. We were just all Americans. And yes my parents, until the very end of their lives, there was no mistaking that they were not native born Americans because they had heavy accents. But I don’t think that they were ever made embarrassed by that. I remember my mother’s frustration [when] we were getting gas at a gas station in Montgomery County, Maryland. And the guy who was pumping gas said, “Where are you from?” having detected an accent. And my mother said, “Washington.” And the guy said, “No, no. Where are you really from?” And so my mother said, “Chevy Chase.” And the man, about to give up said, “No, no. Where are you from originally?” And so my mother, kind of fed up and giving up, said, “Budapest.” But her first inclination was to say “I am from Washington.”

TCG: And do you think that, all of your family who are here, that they feel part of the American experience? Do they feel like they had provided anything that kind of intertwines to this American story? To this American, I don’t want to say dream because it varies, but they felt a part of all of that?

Kati: I think they most definitely felt that they were making a contribution. My mother became a beloved teacher in Montgomery County, Maryland. By the end of her career there as a teacher, she was setting the language curriculum. Having started without any experience, but she went off. She would leave every summer, leaving us unhappily with our father, who didn’t know how to cook. But that forced us to learn how to cook at a very young age. My mother went off to various colleges to be certified as a public school teacher. [She was] always improving on her status until finally she had a PhD, she was Dr. Marton who set the curriculum. So, for sure, she felt as a very proud American. And my father became a very respected journalist. My father actually met my future husband, Richard Holbrooke, at the State Department long before I did. In those days Richard, who became Ambassador to the United Nations and the peace maker in the Balkans, was a young diplomat. He and my father knew each other in the corridors in the State Department. So, I think both my parents felt extraordinarily fortunate in our ability to restart and remake our lives. And in retrospect, I think that the going was good.

TCG: You are quite a renowned author yourself, you’ve written a lot of this down. What do you think the importance is of hearing these stories, of other people hearing your story, reading your story? What kind of impact do you think that can make and why should we keep listening?

Kati: Well, I have never thought of myself as any type of role model for anybody. My children will tell you that I will not place myself on any kind of “look at me” pedestal, because I think that we’re all human and we’re all figuring stuff out for the first time. And I don’t know anybody who’s got it all figured out. I know that at my stage in life I am still trying to get my barrings and trying to make the most out of my good fortune that I have. And I do feel extraordinarily fortunate despite losses in my life. And if there’s something that I’m proud of, that I like to encourage young people to follow, it is to just be very stubborn about what you want to achieve. And not care particularly about winning everybody’s approval to achieve your dreams because it’s not going to happen.

And obviously for a woman in the news business, which I set my sites on early, there were a great many hurdles and sexism was so rampant. It was just assumed that I was going to cover consumer affairs and stories about the wives of great men, and not the great men. And I wasn’t having that. When there was an opportunity I would say “send me” and they did. But it was always stressful. And I would always say that it was more the sexism than the refugee thing that held me back in the news business. It was more that you were stereotyped but I think I had an advantage in that. I was a refugee and already, I was a survivor. And already, I had experienced separation at a very young age - now we call it tender separation, I was a victim of tender-aged separation. Because my parents were arrested when I most needed them, as a little kid at the age of six. I survived that. And so I knew that I could survive pretty much anything.

If i had a leg up on this whole business of getting where I wanted to go, it was that early hardship, which didn’t break me. And coming here and having to remake our lives in a situation where everything was unfamiliar, everything. My friends were all in a different country. My dog was in a different country. And [I had] extremely distracted parents who were trying to figure stuff out, trying to pay the rent too, because we had no savings. We had no furniture. We had to start like my parents were a couple of newlyweds- we all went shopping for a couch. So it was not easy, but I feel lucky in retrospect, when I consider people who were raised in more privileged circumstances, who just don’t know how to cope when things go south, as ultimately they do because in real life there’s loss and deprivation. We’re going through a hardship now as a nation and it’s upsetting but I’m not going to crack under it. And I’m going to keep on writing my books and speaking out. And I think we all have to do that and I do have that singular advantage that I came here and there was no choice. We arrived [in America] in the spring and by September I was in a public school learning a language that I had no background in.

TCG: You mentioned the hardships that we’re going through as a nation. A lot of it, the immigrant rhetoric. Could you comment on what it means to be American today? And what do we as Americans need to do, to bear in mind when we think about our own history and the histories of immigrants coming to our country now?

Kati: I think that we’re more humble people now, we should be because we’ve demonstrated that we’re not the exceptional nation. We’ve been patting ourselves on the back for such a long time that we’re an indispensable nation, we’re a model nation, we’re better than everybody. Well, guess what? We’re not. We’re just as prone to the nasty side of the human experience as any other nation. And that, hopefully, our present political situation will change, but we can’t undo that because the administration that is in office now, we put them there. And we’ve demonstrated to the world that we’re willing to empower people who have so little respect for their fellow man and woman. So, we can’t undo that. That train has left the station. It’s the end of our innocence, if you will. I think that with our new found humility, we should, if anything, embrace new arrivals now more than ever because they have a lot to teach us. I think that my parents were great models for how to be a good American. And I learned a lot from them and I’m hoping that my kids will learn from me. My kids, who have no self-importance and no sense that “I’m an American, so therefore I’m cool”. I think that humility that we passed on to our kids, which my parents passed on to us, is really important for Americans now.

To learn from others and to accept that we’re all in this together and if anything, the planet has gotten so much smaller and the problems cannot be walled off one from another. And the idea that you can solve anything by building a wall is so crazy. When we share the air, we share if there’s hate in the land, no wall is going to protect us. So it takes ownership of what America has become. This is not [just] a bad dream, it is a bad dream, but it’s our current reality and we can’t wish it away. We, and particularly the next generation of Americans, have got to find a way back to our original values so that families like mine will continue to want to come here. But right now, I know people who don’t want to come here because they’re afraid. They’re simply afraid that this country has lost its bearings. We’re even debating what Emma Lazarus said, which is on the pedestal of the State of Liberty. We’re debating whether or not that was added later or did she really mean that? “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses”, we’re debating that. This is a moment for us to really pause and reflect and embrace new arrivals.

You know, I don’t want to give the impression that I am in a state of despair about America because I’m not. I just think that we have lost our innocence and I think that it’s a moment for a reality check. We’ve got to stop fooling ourselves that this will all go away. We’re going to wake up and this will be over because we’ve revealed a side of ourselves that I wish we wouldn’t have been confronted with but we have been. And we have to talk about it honestly and openly. We can’t wish it away. That is now our most important task is to figure out how to talk to each other in a more civil way and to accept our differences. If we accept our differences, then families like mine will keep coming because this is still the most spectacular land in the world with the most to offer. I will always be grateful that my parents brought me here on my birthday to restart our lives, because it is still in my view the last best hope of mankind.

TCG: You’ve devoted so much of your career as a journalist and telling your own stories through storytelling. Do you think there’s a benefit to looking back and hearing each other’s stories?

Kati: We absolutely have to tell stories. I think that telling stories is what separates human beings, Homo Sapiens, from all the other species with which we share this planet. We tell stories and we have to continue to not only tell stories, but to learn from our stories. If we don’t, if everything in this world strikes us as “Oh my God, this is happening for the first time!” then it means we’ve learned nothing. It means that we haven’t been paying attention and that means we’ll just keep going around and around the hamster wheel. If we don’t listen to our stories, and by that I mean if we don’t pay attention to our history, we’re just going to be thrashing around uselessly and repeating the same ad infinitum. The same mistakes will keep blundering. The same never ending wars and not learn from the terrible, some of the terrible mistakes of our history. So history, storytelling, paying attention to each other’s differences and learning from each other is frankly the only way we are going to get out of this huge mess we find ourselves in now.

I do a lot of human rights stuff and work with refugees. And of course, foremost, work on free press advocacy through the committee to protect journalists. It’s very challenging to go to countries where I used to go for Human Rights Watch and for the Committee to Protect Journalists, and meet with the bad guys who would meet with me, because I was representing an American organization. And to say to them, “Look, you can’t do this. You can’t jail journalists! You can’t muffle the voices of opposition.” I mean, they look at me now like, “You’re telling me? You guys are telling us how to behave? Look at yourself!” So we’ve lost a tremendous amount in this current environment. We really have lost more than our innocence. We’ve lost our ability, really to make others uphold values that we hold dear. How do we do that? We’ve lost our credibility. That is a loss.

About Kati:

Kati Marton is an acclaimed journalist and author, as well as an activist advocate for human rights and the freedom of the press. She is an award winning former NPR and ABC News Correspondent, the former chairwoman of the International Women’s Health Commission, a director of the Committee to Protect Journalists, and a member of the Council on Forign Relations. Marton has published eight books, which have been translated into five languages. Her Cold War Memoir Enemies of the People: My Family’s Journey to America was a National Book Critics Circle finalist in 2009.

My American Story: Richard Werthamer

A scientist, executive, and Harvard grad, Richard hails from an Eastern Europe background. His grandfather was a prominent Socialist in the midwest in the 1920’s, who served as a Milwaukee city councilman, before becoming a lawyer.

All of my grandparents came to this country from Eastern Europe in the late 19th century. Some arrived from a German-speaking area, the rest from Russian-speaking, still further east, They settled in the Chicago/Milwaukee area. Those on my mother's side became relatively successful economically. Her father was a real estate developer and her mother was the daughter of an insurance broker. On my father's side, less so: a tobacco shop proprietor. My maternal grandfather made a particular impact: while dealing in real estate, he entered politics (as a Socialist, prevalent in the 1920s upper midwest), and served several terms as a Milwaukee city councilman, before becoming a lawyer.

Although both of my parents attended college, neither was able to complete a degree. Nevertheless, they strongly encouraged my college and graduate education.

I am retired from a career that concluded as the Executive Director of The American Physical Society. Previously, I held managerial positions overseeing technical development in several large corporations, and served as the CEO of the New York State Energy R&D Authority. I hold a PhD in theoretical physics, and spent the first decade of my career doing published research at Bell Laboratories.

Richard Werthamer is retired from a successful career as a scientist and executive. Prior to the start of his professional career, Mr. Werthamer was summa cum laude graduate from Harvard and earned a Ph. D. from the University of Berkeley. He was most recently the Executive Officer of The American Physical Society: the world’s leading membership organization for the physical sciences. Further, Mr. Werthamer has a wealth of experience in senior management, research and development positions for corporations such as as AT&T, ExxonMobil and Becton Dickinson. He was the first recipient of the APS Congressional Fellowship and served as Chairman and CEO of the New York State Energy R&D Authority.

My American Story: Kim Brizzolara

Kim’s grandfather was born in Milan to a family in the textile business but immigrated to the US to find his own fortune. He got a job at the antacid company Brioschi, one of the few businesses in New York that would hire Italian immigrants. Eventually he ran Brioschi--and did so well he later bought the company.

My paternal grandfather, Giuseppe Brizzolara, was the youngest of four children. He was born into a prosperous Milanese family, in the late 1800's. His family owned textile mills and were involved in banking. The eldest son inherited the businesses, and so my grandfather decided to seek his fortune in the United States.He came to New York City, with some contacts, and eventually managed the New York offices for the family that owned Brioschi, a stomach antacid business based in Milano. At that time a unique product with dedicated Italian consumers. The offices were on Varick. Street in Manhattan. I was told years later by someone who had worked for them, that it was one of the only businesses hiring Italians at the time.

Later, my grandfather became president of the Italian-American Club of New York, and there he met my grandmother. She had come from Verona, and worked as a translator for Italian banks. They both were intensely frugal-- except for when, once a year, my grandfather would splurge on a new Cadillac.

They eventually saved enough to buy the company, Brioschi. Many of their friends, mostly Italians, worked in the ad business on Madison Avenue and created a memorable jingle that many people old enough, remember to this day. They had two boys—my father and uncle—who grew up to run the business. My grandfather was philanthropic in his older years, giving most to the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, an institute that was a major supporter for Italian immigrants to the US. founded by Mother Cabrini, whom he had known in Italy.

At around the same time, my mother's father, David Church began his journey to the United States. He fled Ireland as a teenager, after—as I’ve been told— an IRA shooting. He came through Canada and ended up in New Jersey. My maternal grandmother Mary Murnane came from Ireland as a young girl and was a private cook for the actress Rosalind Russell, in Connecticut.

Some years later, at a dance school in Patterson, NJ, my parents met each-other.

Kim Brizzolara is a film producer and private investor; and serves as an advisor to several non-profit organizations. She is Executive Vice Chair of the Hamptons’ International Film Festival, where in 1999, she co-founded the signature program "Films of Conflict & Resolution", which she continues to oversee, Ms. Brizzolara is a Trustee of Glasgow Caledonian University/NYC, which focuses on sustainable business practices, and serves on the boards of the We are Family Foundation, Creative Visions, The Sunny Center/ Ireland for Exonerees, and the Women's Leadership Board at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

She started her career as a journalist with the Philadelphia Inquirer, and has written for numerous magazines and the New York Times. She later worked with Kerry Kennedy at the Robert Kennedy Center for Human Rights. Inspired by her Irish heritage, she focused philanthropically on the area of international conflict resolution., and is a Claddaugh Circle member of the irish Arts Center. She served as a grants maker for the Threshold Foundation, working on peace and national security issues; as acting director of the Coexistence Center at Baruch College School of Public Affairs, and worked on various political campaigns

Kim Brizzolara

My American Story: Alan Patricof

His parents fled the hard conditions of Czarist Russia to live better lives in America

by Alan Patricof

My parents’ family came to this country to flee the pogroms initiated by the Russian Tsar -- somewhat like the story of Fiddler on The Roof. I actually have the ship’s manifest of the boat on which they came over, in steerage.

My father immigrated to the United States from Smila, Ukraine (then Russia) in 1907 at the age of 4. An uncle brought him together with his four sisters and one brother, arriving in Ellis Island before taking a train to Middletown, Ohio. They lived with his mother’s sister who had emigrated from Russia many years before. My mother came over separately in 1911 from Mogilev, Russia, also in steerage. She travelled directly to Waterbury, Connecticut, with her parents, two sisters and a brother.

My father was an orphan when he came over and lived with a total of 14 children, all brought up by his aunt who had two children of her own. I understand it was not that unusual in those times for relatives escaping the pogroms to come to America and move in with relatives who preceded them. Times were tough and people struggled to make ends meet. At some time in the 1920s my father moved to New York City to follow his brother who offered him a job at the the textile business he had set up.

My father met my mother in 1931 and they married in 1933. He joked that he always said he married my mother for her money- “She had $10 and he had $5”.

Before coming to New York, my father worked on a tramp steamer out of Catalina, California, on a canning line in Monterey, shoveled coal, swept sidewalks and delivered papers by bicycle which in those days were delivered before 4am.

Both of my parents went to college, but I never truly knew if they graduated. At least for my father I know Ohio State and Columbia were places he referred to often.

My mother’s father, my grandfather, was a watchmaker, who had a small shop that he ultimately moved to New York City. I can still see him now with the loop he used to look into watches, sitting on his small piano stool, revolving around to meet a customer who came in while he was working.

“In the 1990s [I had the opportunity] to stay in the Lincoln Bedroom at the White House...I couldn’t help reflecting that it was not that long a journey from my parents arriving in steerage in 1907.”

None of my father’s siblings did very much with their lives, but my father sought out a living through the Depression in the remnants business on Bond Street that at the time was one block from the Bowery and a hangout for derelicts and drunks on the sidewalk. Today this area is cluttered with luxury high-rise condos and top end restaurants - if he could see Bond Street today, he clearly would have no recognition. After WWII, he ultimately became a stockbroker, which was a much easier and more profitable way to make a living.

My mother’s younger brother studied law and became a New York State Supreme Court Judge, which was the crowning achievement of this immigrant family. Neither my father’s or mother’s other siblings ever did much with their lives. However, all of their children went on to successful professional lives in teaching, law, medicine and finance - my career being in the latter. The next generation, including my children, have built even more successful careers.

As I think of my own life, I think of the opportunity I had in the 1990s to stay in the Lincoln Bedroom at the White House. At the time, I couldn’t help reflecting that it was not that long a journey from my parents arriving in steerage in 1907 to 85 years later, my sleeping in the White House – only in America.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Alan Patricof is the founder and managing director of Greycroft LLC. A longtime innovator and advocate for venture capital, Alan entered the industry in its formative days with the creation of Patricof & Co. Ventures Inc., a predecessor to Apax Partners – today, one of the world’s leading private equity firms with $41 billion under management. In 2006, he founded Greycroft Partners, a venture capital firm, to invest in leading early and expansion stage investments in digital media. He has helped build and foster the growth of numerous major global companies, including, among others, America Online, Office Depot, Cadence Systems, Cellular Communications, Inc., Apple Computer, FORE Systems, NTL, IntraLinks, and Audible. He was also a founder and chairman of the board of New York magazine, which later acquired the Village Voice and New West magazine. From 2007 to 2012, he served two terms on the board of Millennium Challenge Corporation, having been appointed by Presidents Bush and Obama respectively. From 1993 to 1995, he served as Chairman of the White House Conference on Small Business Commission in The Clinton Administration.

My American Story: Allen Hyman

Allen Hyman’s family escaped Russian-Poland to avoid his 12 year old uncle being drafted for 25 year, and had a long dangerous journey to the USA…

by Allen Hyman

My immigrant story is about my mother. She was born in a shtetl in Poland-Russia. At that time it was led by the Czarist government - they were cruel, oppressive and overtly antisemetic. About 15 years ago I visited Piatnica, her small village located 50 miles from Warsaw and convenient to Treblinca. There her tiny house still stood. At the time of my visit my uncle was still alive. He clearly described the house where he had lived until he was 8, located on the Narew river.

There were three main reasons for moving to America: overt Jew-hatred, abject poverty and most imminent, the oldest son, 12, was subject to the draft for 25 years. My grandfather left with a caravan of young fathers for NY. He left my grandmother and 3 sons. After 3 years, he saved enough to purchase "schiffcarts" ship tickets for his family. My grandfather had to break the news that he had a daughter, my mother. She was most likely conceived on the night before he left Piatnica. While he was gone, my grandmother supported her family, including her mother by the family "business" of rope making.

My grandparents kept in touch during his absence with the help of a few literate friends who could read and write. I wish I had these letters. Finally the day of departure. My grandmother said good-bye to her mother, knowing she would never see her again. She brought some clothing for herself and four children, feather down pillows, quilt, a few pots, candlesticks and remarkably, food for the three week trip. They were kosher people.

They travelled to Antwerp from Warsaw by train. They had to skip Hamburg, a nearer port, because the Kaiser, Czar's cousin, would have sent them back because Sam, the eldest son, was escaping the draft. They didn't have passage for any specific ship. When they arrived at the port, they simply waited for an available ship that would accept their Schiffcart. There was always room for one more family in Steerage. I always imagine how awful my grandmother must have felt living in an overcrowded tenement, teaming with vermin, noisy and cold in winter and steamy in summer. Although her Piatnica home was primitive, at least it seemed bucolic compared to the lower east side of New York.

“ I wish I could remember exactly how often she referred to her love for America; a goldener land.”

My mother left school when she was 12 to work; her brothers finished HS and one went to "night" law school. But her family remained very poor, throughout the 20s and the 30s. I lived with my grandmother until I was six. I wish I could remember exactly how often she referred to her love for America; a goldener land. It sounds more compelling in Yiddish. (my father, American born, was orphaned when he was seven and basically never went to school. But taught himself to read and write and basic arithmetic. That's for another story)

About The Author

Allen Hyman has successfully obtained millions of dollars of tax refunds and savings for clients during his distinguished career. He represents both claimants and condemners in Eminent Domain proceedings throughout the State of New York and other jurisdictions.

At Hofstra University School of Law, Hyman has taught courses in “The Law of Eminent Domain and Tax Review and “Pre-trial Skills.” He currently teaches a course in “Real Estate Transactions.” In addition to his role as an Adjunct Professor of Law, he has lectured at the Nassau Academy of Law, the Institute of Property Taxation and the National Institute of Trial Advocacy. He has also authored articles on tax certiorari and condemnation issues in both legal periodicals and the business press.

Active in civic affairs, Hyman serves as a member of the Board of Overseers of Northwell Health. He is a former Chairman of the Board and currently a member of the Board of the Education and Assistance Corporation, a social service organization, which among other things, offers counseling to non-violent offenders as an alternative to incarceration.

Hyman serves on Governor Cuomo’s Judicial Screening Committee for the Second Department. As one of its thirteen members, he is responsible for screening applicants for judicial appointments to all courts including the Appellate Division in the Second Judicial Department. Previously, Hyman served on the governor appointed State Judicial Screening Committee that reviews candidates for the New York State Court of Claims.

My American Story: Eva Haller

At 12 Eva Haller joined the Hungarian Resistance against the Nazi occupation, eventually fleeing to the USA, where she marched in Selma alongside Martin Luther King Jr.

Eva Haller is a Hungarian-American philanthropist, activist, executive and Board Member. She joined the Hungarian Resistance at age twelve to fight against the rising tides fascism and virulent antisemitism plaguing Europe.

When the German occupation of Hungary began in 1944, Eva was sent by her parents to the Scottish Mission in hopes she would be kept safely hidden amongst the students. They charged her with looking after the ten year old son of a family friend. When the Institute was later raided for hiding Jewish children Eva charmed a Nazi officer into sparing them both. Eva remained in hiding for the rest of the war and then later moved to New York.

Eva, a longtime member of The Common Good, sent us an interview to include with her story. Keep reading to hear her discuss her youth in the Hungarian Resistance, fleeing Nazi’s, and championing human rights across the world:

Who has shaped you as an activist and philanthropist?

When I first came to this country, I was as an illegal alien cleaning houses. Then I was no longer illegal because I got a student visa, but I was still cleaning houses. There were a couple of people who befriended me, and supported me, and believed in me.

I believe, very firmly, that the greatest gift you can give to another human being is to share with them the idea that you believe in them. That one-day they will be able to achieve what they are hoping to achieve.

Eva Haller meeting Malala Yousafzai

If anyone asks me, “What’s your identity?” I introduce myself as a mentor — and not as a philanthropist or not even as a social activist — because I have been mentored so well.

I have gotten so much from one friend in particular, her name is Joyce Edward, she’s 96. She’s a social worker; she has a PhD, and taught at Smith College. She not only believed in me, she pushed me to go to graduate school and become a social worker. She’s still proud of me. She’s eight years older than I am, still very beautiful, still very active, and she still believes in me.

The other friend was more on an equal basis. Barbara Pontecorvo, who’s about a year younger than I am. She took me in like a sister; she shared with me her parents so that I felt I had a home. I’m the godmother of Barbara’s three sons. I became part of that family.

Both Joyce and Barbara mentored me by the way they lived. I’m so grateful that the two women are such great women with such wonderful values.

I love my women friends. I cherish them, and I get a great kick out of them. I find it so difficult when I see some of these shrewd women who are against other women, or against the right of abortion and independence. It has to do with economics.

Eva Haller in India.

In India where some mother-in-law throws the daughter-in-law into a fire because by killing the bride, you get another bride with some more cows. Women can be very vicious to women.

Successful women have less to lose. If they are successful they can sit back and be far more generous.

In a society where we are not financially threatened by each other, our feminine values, when they come out, couldn’t be nobler and more wonderful and more supportive.

The most important part of life is validation. How do you validate yourself? It’s important to have a goal and a road map at any age, but it’s the most important to have one when you’re young. Once you’ve achieved something and you achieved it yourself, then you can move on from there because you have validated yourself to a certain point.

That still holds true when you’re 87 years old: Why are you going to get up next morning? What is the reason that you should be still here? That validation cannot come from anybody but you.

That is important because it keeps you working towards self-realization. But now, instead of worrying about how am I viewed, I can help someone else to view himself or herself.

What do you think is needed for social impact in the context of the current political climate? You have said that one thing people could do is to work to support the existing structures.

As a first step, people need to understand what those structures. They need to know what exists and what can be helped within what exists. Most people love to start new organizations because it’s an ego trip. We don’t need an ego trip right now.

The president is teaching us something enormously important. And that is, conventions haven’t worked. The most obvious next step in my mind is to re-examine all the ways we handled things before.

The institutional ways we have built this country are clearly not working. And there is this guy who is showing us that by defying all traditions, he is making a whole new way. Clearly caring about society, institutions, and order is not where he’s coming from. We should learn from the election that it is not a good idea to dismiss him.

You start by clearly examining what this man is doing. What are the steps he’s taking to destroy those things that we built up? Who are the people whom he has selected? What are good organizations we can support?

Here I remember, Ellen Malcolm, one of the IBM heirs, who decided to create Emily’s List. [Before Ellen Malcolm founded Emily’s List 30 years ago, no Democratic woman had ever been elected to the Senate in her own right.]

We have to understand that, even when you get to be 87, like me, social media is our most important weapon — if you know how to use it. I am on the Board of an organization called News Literacy Project (NLP).

It started nine years ago; it had a very hard beginning because nobody cared about it. Suddenly everybody is talking about fake news, “My god, young people have no idea where they get their news from.” They don’t know whether the news they believe is fake, half-fake, or half-baked.

Eva Haller as a young girl in Hungary

In Nazi Hungary there was no freedom of speech, and in Soviet-occupied Budapest there was no freedom of thought. In America today we desperately have to retain, maintain and encourage critical thinking and the courage of our convictions. Therefore, we must protect and grow the News Literacy Project, because news literacy is our most precious insurance against totalitarian slavery of thought

There was a piece about NLP on NPR the other day and the president of our board suggested that we put it on our Facebook page. I think we got 5,000 responses in one day. Yesterday we received $700,000 from the Emerson Collective in Silicon Valley. Our whole budget wasn’t that much! Change in a terrible direction and change in a good direction can happen very fast.

About the Author:

Eva Haller is a Hungarian-American philanthropist, activist, executive and Board Member. Notable positions include Board Chair of Free the Children, Trustee of the University of California, Santa Barbara, co-founder and President of the Campaign Communications Institute of America, Visiting Professor at Glasgow Caledonian University and the 2014 Magnusson Fellow.

A true American success story, Eva started out cleaning houses to support her passions and eventually earned her Masters Degree in Social Work. Since then she has: marched with Martin Luther King; co-founded the Campaign Communications Institute of America; volunteered for UNICEF in Southeast Asia; supported countless arts and cultural organizations with the proceeds of her successful company; worked as board member for News Literacy Project (NPL) and Board Chair of Free the Children.

Eva has earned many awards and honors throughout her life, some highlights of these include: 2011- Recipient of the Mandela Award for Humanitarian Achievement, Rubin Museum of Art, 2013 - Lifetime Achievement Award, United Nations Population Fund, 2013 - Inaugural Mentoring Award, Forbes Women’s Summit, 2014 - Awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Glasgow Caledonian University, 2015 - Awarded Luminary Status at the World Summit of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, and 2017 - Inaugural Ban Ki-moon Mentorship Award.

Sources:

Introduction and bio written and compiled by Isabel Wilson [TCG Intern]

My American Story: Lily Kaye

Born in the USA, Lily Kaye could not understand why her dad was called an “alien” if he was not from outer space. She later learned that term “alien” meant her dad was a foreigner, and as she understood the immigration process she realized how lucky his case was.

by Lily Kaye

I was waiting to be picked up from Kindergarten, trading Kooky Pens -- a strange fad of pens with painted faces on them -- with my friends. I remember bragging to my friend Fei-Tzin as we traded pens that my dad was an “alien.” To me, this was a hilarious statement, and the word alien had only one meaning-- that of a green, long-limbed creature from outer space. I obviously knew that my 6’ 4” father with blue eyes and brown hair was not a green creature from outer space, yet I enjoyed insinuating that he was. At the time, I had no comprehension that the term “alien” meant that my dad was a foreigner, no understanding of the immigration process, or how lucky he is.

My dad grew up in British Columbia, Canada, and moved to the United States for college. Growing up, I was unaware that he had to do anything special to live in New York City, the only city I have ever lived in. It was not until many years after my Kooky-Pen trading days, once my dad became a citizen of the United States, that I began to contemplate what it means to be an immigrant, to become a citizen, and all that it takes to reach the highly-coveted status of American Citizen.

While my dad made the active choice to move to the United States and later become a citizen, it is a privilege I was merely born into. I take pride in my country, am grateful to be an American citizen, but recognize that my status as a citizen is one that should be coveted, one that so many people yearn for.

My dad’s journey to become an American citizen was longer and more difficult than I thought. He had to prove that he had a job waiting for him in the United States, post the job opening in the newspaper, and go through each application to prove that every American applicant was inferior to him in a meaningful way. He had to endure a physical examination, interviews, and wait a painfully long time for results on a background check. If this is the story of an educated, privileged, white, male, I struggle to truly grasp what other people endure to become citizens. I cannot help but wonder what his experience would have been if he were not a white man.

I remain conflicted about my father’s immigration story. Once, in a history class at Duke University called Immigrant Dreams, American Realities, I was asked to discuss an immigrant that I know, and share something about them and their story with my class. I racked my brain for someone to discuss and settled on my childhood babysitter, Ingrid, who immigrated from the Dominican Republic. It was not until after the class ended that I realized I could have spoken about my own father. I then began pondering why I genuinely did not consider him an immigrant with his own unique immigration story. I think I discounted my dad’s story because he faced relatively minimal strife and is an educated white man whose physical journey to the United States was a short plane ride.

“I remain conflicted about my father’s immigration story…I wonder how the word ‘immigration’ can simultaneously apply to his process and that of families separated at the border.”

I have begun to wonder how the word immigration can simultaneously apply to his process and that of families separated at the border, or Irish immigrants who were discriminated against, denied work, and raced because of their immigrant status in the 19th century. By using the same word to describe all of these different journeys, does it diminish the struggles that many immigrants face, does it work to equate the comparatively easy journey my father faced with other tragic ones?

About the author:

Lily Kaye was an intern at The Common Good over the summer of 2019, where she worked on updating TCG’s website, conducting research, and organizing events. She is currently an undergraduate at Duke University studying Public Policy and Economics.